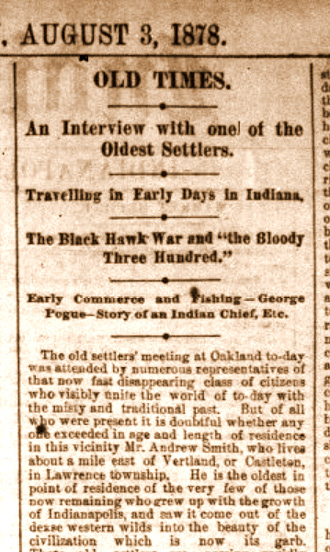

Click image below for full size image

(Transcript Below.)

OLD TIMES.

-o-An Interview with one of the

Oldest Settlers.

Travelling in Early Days In Indiana.

-o-The Black Hawk War and “the Bloody

Three Hundred.”

Early Commerce and Fishing — George

Pogue - story of an Indian Chief, Etc.

FIRST TRIP TO INDIANAPOLIS.

"It was in 1819 that I made my first trip to where Indianapolis now stands," said Mr. Smith. "I was then 16 years old and living with my parents in Two-Mile, Butler county, Ohio, where I was born. My grandfather, Orbison, was an Irish lord, but, joining in one of the numerous revolts against the English government, and of course being defeated, he was compelled to seek safety in flight. He had considerable wealth in a portable shape, and, coming to America, settled in Pennsylvania previous to the revolutionary war. "My mother was only nine months old when he was compelled to flee. My uncle John, about the beginning of this century started on a prorpecting tour, and, getting into the Miami valley, returned with such glowing reports of its beauty and fertility that grandiather was induced to send two of his brothers in John’s tracks to learn whether he was not like one of the ten spies sent into the promised land, who returned with false reports. The brothers returned, corroborated John’s story, a colony of about forty families, including that of my father, a German who had married my mother in Pennsylvania, was organized, and a settlement made where the town of Hamilton now stands. The Indians were still plenty in that neighborhood, and in their association I grew up. Indians were my playmates, and one of them, Lafayette, by bosom friend and rival in all the sports and passtimes of boyhood. When uncorrupted by bad whisky, falsehood and deceit, the Indian is possessed of a noble nature and a true manhood, which I have looked for in vain in the white race. I want no better friend and neighbor than the red man, and deeply regretted the necessity that compelled their departure from this part of the country. The colony in and about Hamilton grew and prospered, and with the spirit of unrest that marked the hardy pioneer of those days, as soon as the country began to be cleared they pulled up stakes and penetrated further into the wilderness. Quite a number of them settled in Marion county, the Negleys and the Jones in the immediate neighborhood of this location, I being of the number, while others pressed on to the Wabash, settling at Lafayette. The father of Henry Taylor, one of Lafayette's most promiueat citizens, was a pioneer from Hamilton."

"Well, John Conner, uncle of A. H. Conner, formerly of Indianapolis, a settler at Connersville, who had moved out with his father to Strawtown, north of Noblesville, where he was trading with the Indians, came to my father's house one day in the spring of 1819, and offered him $500 to haul a load of whiskey and gimcracks such as were used in dealing with the Indians, beads, fancy calicoea, knives and the like from Hamilton to his store in Strawtown. Father didn't take up with the offer right away, but when Conner said to him, "Jim, yon can take your draw knife and other traps with you and make a lot of barrels from the green wood, and fill them with honey that the Indians will gather for you. and sell that when you come back," I saw that the thing was fixed. Father, however, kind of studied over the matter like, not to let John know that he was keen to go. and said he'd give an answer in the morning. Of caurse I knew what it would be, and it wasn't a great while before we were on the road with a wagon load of truck, drawn by six oxen. We followed the "trace" from Connersville up to Andersontown, and then across to Straw town.

Arriving there, father, who was a cooper, made twelve or fifteen barrels out of green stuff, and the Indians did fill them with tree honey in such a little while and from such a few trees, that I told mother after getting home that every tree in Indiana was full of honey. I really believed it at the time. After filling the barrels we started home by way of the trace leading down through where Indianapolis now stands. At Broad Ripple there was a little trading post kept by a Frenchman named Bruitt, who bad been there so long that even his cabin was decayed. We came on down the river until we struck the cross trace, and then started east. When we got to where Pogue's run crosses Washington street an axle broke in the mud. There was a big pond or marsh just there fed by a spring, which will be remembered by many of the later residents of the place. The accident detained us for a day, during which time we put up at a house which occupied the site of Isaac N. Phipps's place in the extreme eastern part of the city. With a new axle we proceeded on our journey and arrived safely at home after an absence of about four months. The trip was exceedingly remunerative to father as he disposed of the honey to good advantage, and besides had his $500 cartage hire. Travelers nowadays would be surprised at the manner in which a wagon such as ours made its way through the woods. There was the trace (it is known as trail to most readers) to give us the general direction but the best route alongside was picked out for the vehicle. Occasionally we'd have to cut a path through the underbrush or hew down a tree. Saplings no bigger than that-(indicating a healthy, vigorous maple about six or seven inches.in diameter) we rode down. Trees in this country mostly have their roots ou or near the surface, and six oxen can pull over a pretty good sized shoot. The next year I returned to the vicinity of Indianapolis and settled with my uncle on a farm near Waverly."

A DANGEROUS GUN.

Noticing that Mr. Smith was minus his left hand, the reporter inquired how he lost it, and in response learned something about an early celebration of the Fourth of July on the new purchase. On that occasion (1830) as had been the custom for several years, the Sunday schools were celebrating under direction of Col. James Blake, and the citizens under Demas McFarland. Mr. Smith had not expected to be present as he was hard at work on Gen. Hanna's farm, but about noon a rain drove him out of the field. He then came down town, and finding that some of the boys were firing an old cannon advised them to stop, as the weapon was cracked and in a dangerous condition. They did so, and he then went to dinner in company with a number of young associates, and while yet in ths house a number of persons interested in the citizens' celebration came up and found fault with his stopping the firing of the gun, charging that he did it in the interest of the rival gathering. He denied this, and said this unjust accusation was not due him, and offered to go with the crowd to Bates's grove, on East Washington street, where the celebration was in progress, and superintend the firing of the gun in response to the toasts. Twice the old shell was fired safely, but at the third round, which followed the second immediatey, in an attempt to give a double salute, a premature explosion occurred, and the ramrod carried away Mr. Smith's left hand. He does not know to this day how the accident occurred, and has long since given up trying to account for it. Two years later the same gun, in attempting to fire a salute on he occasion of the departure of the "Bloody three hundred," in the Black Hawk war, blew off both the hands of Samuel Warren. The death dealing instrument was afterward shipped to Lafayette, where it wound up its career by killing two men, who were attempting to fire it, and then it was sunk in the Wabash river.

THE BLOODY THREE HUNDRED.

Mr. Smith's allusion to the "Bloody three hundred," occasioned an inquiry as to the organization of that bodv, of which the reporter, during a residence of seventeen years in Indianapolis, had never heard mentioned. Thereupon he was favored with a short account of it, which so nearly resembles that of Mr. B. R. Sulgrove in "Holloway's Indianapolis," to which his attention was directed, that that is reproduced here, as better than the reporter can give. Mr. S. says:

The spring of 1832 brought with it nothing inportant. But in June came news of the Black Hawk war, and the then celebrated "Bloody three hundred," who deserve a place beside Tennyson's "Six hundred," was organazed to represent Indiana in the fatal fields of that last of the Indian wars east of the Mississippi. One hundred and fifty mounted men of the fortieth regiment of militia and as many from the regiment in the adjoining counties were called for by Col. Alexander W. Russell, and rendezvoused in the grove on Washington street where John Carlisle's residence now stands, (corner of West) then a part of the military ground. They came with the regular equipments of Indian fighters - backwoods rifles, tomahawks, a pound of powder in each man's horn, and a buckskin "shotpouch," with an adequate quantity of bullets. They were organized into three companies under Captains J. P. Drake, J. W. Redding and Henry Brenton. Colonel John L. Kinnard was one of the party. Col. K., was subsequently elected to congress over W. W. Wick, and was blown up in a racing explosion on the Ohio, on his way to his second session of congress and was scalded to death. He was one of the most popular, and decidedly the most promising young man ot his day, in the state. He began as a school teacher. The morning before the march to Chicago the grove was full of boys throwing tomahawks, and soldiers preparing arms and knapsacks. The street (for there was but one) was full of crying women and wondering children, and Col Russell as be rode up with a big sword in a leather scabbaid, was regarded as a second - not a third - Napoleon. The "Bloody Three Hundred " marched for Chicago, but never got any further. They met no adventures, and did no duty except marching, and came home again covered with dust if not glory. It was told of them, at the time, that one of them, who was standing guard at night up near the Lake, got frightened at a cow and fired, raising an alarm and bringing out the whole valorous host to the perilous encounter, but it was probably a calumny. The war was ended before they "got a smell." They got back on the 3rd of July, and had a share of the celebration and dinner the next day, where they were regarded as "veterans." They were guided — for there were no roads up north in those days — by Mr. W. Conner. He was certainly capable, if any man was. The troops were paid in the January following, by Major Larned.

Although, as Mr. Smith says, the troops never went farther than the Kankankee river, and the expedition amounted to nothing more than a big fishing and hunting excursion, the survivors are now allowed, and are drawing a pension. Appropos to this Mr. Smith tells of a conversation that occurred a few years ago between S. A. Fletcher, sr. and John Chill, watchman at the courthouse, then in course of construction, who were members of the "Bloody Three Hundred." Said Mr. Fletcher to Mr. Chill, as he passed by the court-house on his wav down town:

"I see, Mr. Chill, that congress has determined to give the survivors of the Black Hawk war a pension."

"So I read in the paper this morning," said Mr. Chill. "Well, I'm very glad of it," continued Mr. F., "for we need it."

And to this day Mr. Chill doesn't know whether his old companion in arms was dealing in sarcasm or not.

LAFAYETTE'S STORY

Mention was made at the beginning of this article of Lafayette, one of the Miami Indians with whom Mr. Smith used to associate when a boy and who was his chosen playmate. From the time the Miamis moved to the Piqua reservation until the year 1836 or 1837 Mr. Smith lost sight of his old companion and expected never to see him again. At that time the Miamis were again moved, this time out west, and en route they passed through Indianapolis, stooping on McCarty's farm during their stay. Mr. Smith was then deputy sheriff, and one day when going home to dinner he heard his name called. Looking up into the window of one of the rooms of Ray's hotel he espied Lafayette. Rushing up to greet his old friend he was paind to observe that be was under the influence of liquor and that the table was covered with liquors of all kinds. Lafayette's story was to this effect: After the the tribe had been located on the Piqua reservation he was sent to school and thoroughly educated. Returning to his people, he married an educated squaw and raised two children, noble specimens, according to Mr. S. Mrs. Lafayette was an amiable, lovely woman, and the entire family dressed in the costumes of the white people, nothing but their color remaining to betray their origin. Lafayette had engaged in trading and became very wealthy, so wealthy indeed that when the tribe moved west he was enabled to pay two barrels full of silver dollars to the council for a release for himself and family for the right to remain among the whites and continue his manner of living. After the tribe had departed the chiefs repented of their bargain and sent back runners to notify Lafayette that in five days he must close up his business and follow them. He knew that in case he refused be would be killed, so he deliberately set to work to drink himself to death, hoping to accomplish it before the journey ended. Mr. Smith, after the first greetings were over, insisted on Lafayette coming the next night to take tea with him and coming sober. For the sake of old friendship Lafayette agreed and told his wife to put away the liquor, he would keep faith with Andy. He went, according to agreement, and the result of the visit was that he waa domiciled at the Smith house while his stay in Indianapolis lasted. In a day or two Mr. Smith had a long talk with the chief, for his guest was a chief, and remonstrated with him upon his conduct. He told Lafayette his people had educated him that he might be of service to them, and that his first duty was to the tribe, especially now that they had need of him. To do as he was doing was cowardly and unmanly and not worthy a good Indian. Lafayette heard the appeal, and determined to follow his friend's advice. That evening he announced his determination to his wife, and a happier woman, Mr. Smith says, he never saw. The next morning he and his wife accompanied their guests six or eight miles on their western journey, and bade them on affectionate adieu. That was the last he ever saw or heard of Lafayette, but such trust does Mr. S. put in Indian rectitude that he is satisfied the chiefs promises were carried out to the letter.

As showing the fidelity of Indians to old acquaintances Mr. Smith mentioned the experience of his son James, who was seized with the Pike's Peak fever in 1858-9; and in company with a number of young men. including George Yandes, W. H. Roll and others, started for that Eldorado. Before going Mr. Smith gave him letters to several of the old Indian chiefs, many of whom he knew only by reputation, others he knew personally and upon presentation of these young Mr. Smith and party were assured of immunity from danger at a time when white parties were being constantly surprised and assaulted, and promised guides whenever they were in need of them. These assurances and promises were kept, and Mr. Smith subsequently guided several parties from Ft. Lenvenworth to the Peak without danger. He afterwards settled on a farm in Iowa, where he died.

POGUE AND MC'CORMICK.

Holloway's Indianapolis devotes some space to a discussion of the claims of George Pogue and John and James McCormick as the original settler or settlers of Indianapolis, and the author is inclined to give the honor to George Pogue. This question has been one of interest to the reporter, and he questioned Mr. Smith for his opinion. He says that the McCormicks undoubtedly reached here first, and something seems to have "soured" the old gentleman on Pogue, altogether. He says that Pogue was a man of no particular merit, and that his pretended disappearance and death at the hands of the Shawnee in 1821, which occurrence led to calling the creek that has since borne his name by the title by which it is known to-day, was only a fiction. Mr. Smith claims that Pogue returned to the region whence he originally came to Indianapolis, and war beard from a number of years afterwards. The cause of his sudden and mysterious leaving Mr. S. does not give.

"'SANG" AND FISHING.

Mr. Smith entered somewhat into detail of the preparation of a root which formed a large part of the commerce of Indiana in early days, but little heard of now,—ginseng, or "sang" according to the vernacular. Col. James Blake dealt very largely in this, and purchased all that was produced for miles around. It brought good prices, a dollar a pound, and families frequently made $12 and $15 per day. The root was boiled and dried; the latter being done in homes prepared especially for that work, in which an enormous temperature was maintained. The root had to be turned on the dryers occasionally, which required the services of men inured to the intense heat that prevailed. By practice some of the men were enabled to enter the building without much discomfort, seeing which green hands essayed to follow them. A gasp or two would be given and the poor fellow, oftener than not the victim of a practical joke, would fall senseless and unless immediately hauled out in the open air would have perished. The ultimate result of the process of curing "sang" was a liquid clear as honey, which brought pound for pound—that is, pound of silver money for a pound of the "sang." About six pounds of the root would make one of the liquid, so that its preparation was quite remunerative. But its use has gone out of fashion of late years, and the sign "beeswax and ginseng," so well known formerly is no longer seen.

In early days the streams in this vicinity were richly stocked with all kinds of fish, and the veteran recounted several experiences in his pursuit of the sport of fishing, which indicated that the angler of the present day is no improvement on his predecessor in the matter of story telling. The reporter's bump of veneration is highly developed, hence he avers belief in the tales told by the old gentleman of the "catches" of a wagon load of fish in an afternoon. Most of the sport was enjoyed near Waverly, which has always had the reputation of being an excellent fishing place. Mr. Smith's relation of how the biggest bass ever produced in White river, which was hooked and brought to shore by Mr. Hightower, an old stage driver, and finally got away in a thoroughly exhausted state through Hightower's obstinacy, is worth hearing, but will not bear repetition in print. From all accounts the streams in earlv days undoubtedly were a bonanza to the enthusiastic angler.

Mr. Smith is a hale old gentleman of 75, and is apparently good for twenty more years of life. He shows his Irish lineage in appearance and manner, and even more distinctly in conversation, making him an agreeable and entertaining talker. After leaving Waverly he came to Indianapolis, where he remained until 1852. He was engaged in farming most of the time, but served, as deputy sheriff for several terms, and is inseparably identified with the old jail. He also dealt in stock, but was unfortunate in his speculations. He married the daughter of John Hanna, sister of the father of Hon. John Hanna, and raised a family of sevaral children. All are now dead, including his wife, except Robert L. Smith, the well known attorney. In 1869 he married a second time. His residence is in a pleasant grove, opposite a large tract of woodland, containing the largest pine trees in the country, which he planted the next year after removing from the city. The visit to the farm was heartily enjoyed by the reporter, who trusts that his venerable host will be spared for many years to come.

-o-

Comments (0)